Welcome to Women’s History Month! March 8 is International Women’s Day, and we can’t help but take this opportunity to celebrate women who have advocated or blazed trails for language rights throughout history. Some of these women made amazing contributions to preserving their languages and cultures. Some fought for speakers of minority languages to enjoy the same rights as their peers. And some changed the way people learn, speak, and write for good! Here are some of our favorite figures in language history!

Adelina “Nina” Otero-Warren (1881-1965)

Nina Otero-Warren’s name is popular as a crossword puzzle clue: “Suffragist who advocated for bilingual education.” But her role in history is even more interesting! Born into a wealthy family of Spanish heritage in New Mexico, she grew up speaking both Spanish and English. When she became involved with the women’s suffrage movement, she insisted materials be printed in Spanish as well as English. It was important to her to involve as many potential voters in the suffrage movement as possible.

During a time when people who spoke languages other than English were typically forced to assimilate, Otero-Warren advocated for bilingualism. When she served as Superintendent of Public Schools in Santa Fe County (making her the first woman to hold the position), she defied a federal “English only” mandate to allow students to speak Spanish without punishment and to allow Spanish language and culture education through the arts. In 1922, she became the first Hispanic-American woman to run for Congress, becoming the Republican nominee for New Mexico’s only seat in the US House of Representatives. And yes, she campaigned partly in Spanish!

In 2022, Otero-Warren became the first Hispanic American featured on US currency as part of the American Women quarters series!

Mary Kawena Pukui 1895-1986

Mary Abigail Kawenaʻulaokalaniahiʻiakaikapoliopele Naleilehuaapele Wiggin Pukui, typically known as Mary Kawena Pukui, was born during a time of change. The Hawaiian monarchy had fallen and opportunities to practice Hawaiian language and culture were limited. Growing up, Mary’s grandmother and mother raised her in the Hawaiian language and tradition, while her father spoke to her only in English despite being fluent in Hawaiian. Even as a teen, Mary made it her mission to preserve her language and culture, collecting oral histories, stories, and songs. She taught Hawaiian to children and, later, adult scholars, and served as a translator. She co-authored countless papers and books, including the Hawaiian-English Dictionary, Place Names of Hawaii, and collections of Hawaiian songs, chants, and folklore. She also published a two-volume guide to Hawaiian traditions called Nānā i ke Kumu, Look to the Source.

By the 1970’s a Hawaiian language Renaissance had begun, and many credit Mary with helping to make it possible. In addition to her amazing contributions to Hawaiian language and traditions, she was also an accomplished composer and hula expert! She’s featured in the Hawaiian Music Hall of Fame and Hawaiʻi Magazine’s list of the most influential Hawaiian women!

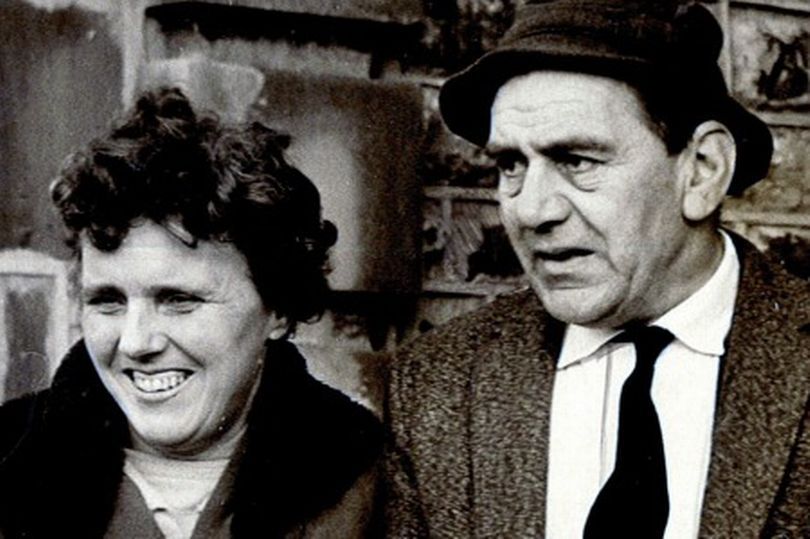

Eileen Beasley (1921- 2012)

Eileen Beasley may have seemed like an ordinary teacher and housewife, but her strong will and campaign of civil disobedience marked her as an important advocate for the Welsh language. In the 1950’s, the Welsh language had no official status in Wales. This was nothing new; Welsh language bans in the 16th and 18th centuries made it hard for Welsh speakers to represent their country or have fair court cases. Eileen and her husband Trefor decided not to pay taxes until they were issued in the Welsh language. After all, Welsh was their first language and they lived in a majority Welsh-speaking village. Why, then, shouldn’t official communications be issued in Welsh?

Due to their civil disobedience, Eileen and Trefor went to court 16 times and even had many of their belongings confiscated. Still, they wouldn’t give up. It took 8 years, but in 1960, the council finally issued the tax bills in Welsh. In fact, two years before that, Eileen was elected to that very council as a member of Plaid Cymru (the Welsh Party). There, she continued to push for the presence of Welsh language in all official communications. Welsh language advocates hailed her as the “mother of direct action” and emulated the Beasleys’ civil disobedience across the country. Today, the Welsh language proudly features alongside English almost everywhere in Wales, from street signs to election ballots.

Marie Jean Philip (1953-1997)

Language rights often cross over with other kinds of accessibility rights. Marie Jean Philip’s American Sign Language advocacy is a great example of that. For many years, schools for Deaf children forced students to speak and try to lip read instead of using sign language, making it much more difficult to communicate. Born into a Deaf family, Marie Jean Philip was rejected from the Clarke School for the Deaf because of her use of sign language. She went on to attend the American School for the Deaf and Gallaudet University, where she was allowed to communicate in her first language. After working as an ASL researcher, teacher, and interpreter at Northwestern University, she became a major advocate of the Bilingual-Bicultural movement. This means allowing Deaf students to use ASL as their first language and English as their second (or third, fourth, etc.), educating them in both languages and fostering Deaf culture.

In her work at The Learning Center for the Deaf in Massachusetts and beyond, Marie Jean Philip helped establish ASL as a recognized language and advocated for the rights of Deaf children and adults. Today, the Learning Center for the Deaf’s PreK-12th grade program is called the Marie Philip School.

(YouTube)

Maya Sekine (Today)

Ainu is one of the most critically endangered languages on Earth. Only around five fluent native speakers of this indigenous Japanese language remain, most of them quite elderly. For years, the Japanese government forbid students to speak the Ainu language in schools, and many people hid their ancestry due to the stigma. Some researchers believe that most Ainu youth today are not even aware of their own Ainu heritage. One person this cannot be said for is Maya Sekine, a young woman living in the town of Biratori.

Raised by an Ainu mother and a father who teaches the Ainu language, Maya runs a YouTube channel to help document the language. Ever since she was a teenager, she’s helped lead Ainu workshops, gave Ainu lessons over the radio, and even recorded bus announcements in the language for Biratori! Together with her family, Maya is doing the important work of keeping the Ainu language alive!

FOR FURTHER READING: NOTEWORTHY ACADEMICS TODAY

Language advocacy is an ongoing process. If the fields of language advocacy and bilingualism interest you, here are some modern-day scholars whose work covers everything from multilingual education to language diversity.

Uju Anya: An associate professor of Second Language Acquisition at Carnegie Mellon University, Uju Anya describes herself as a “scholar of language learning and Black experiences in multilingualism.” Dr. Anya studies how race, class, gender, culture, and other identities influence language learning experiences. She’s published two books, Racialized Identities in Second Language Learning: Speaking Blackness in Brazil and Racial Equity on College Campuses: Connecting Research to Practice.

Luisa Maffi: Combining together linguistics, ethnobiology, and anthropology, Dr. Luisa Maffi’s studies focus on the importance of both biological diversity and cultural and language diversity. In her words, “There is a converging extinction crisis of biodiversity and cultural/linguistic diversity. These two phenomena are happening along similar lines, and we think that they are indeed interconnected.” Just as the conservation of endangered plants and animals is important, the conservation of endangered cultures and languages is, too. Dr. Maffi is a co-founder and Director of Terralingua, an organization dedicated to sustaining biocultural diversity.

Kate Menken: How are English language learners left behind by standardized tests? Kate Menken, a Professor of Linguistics at Queens College of CUNY, is interested in exploring that question. She studies language education policies, bilingual education, and the experience of multilingual students in public schools. Menken is also a research fellow at the Research Institute for the Study of Language in an Urban Society at CUNY and a co-editor of the journal Language Policy.

Tove Skutnabb-Kangas: A Finnish linguist and former professor, Dr. Skutnabb-Kangas has written or edited approximately 50 books and published about 600 articles. She’s best known for creating the word ‘linguicism,” or language discrimination, a topic of deep academic interest for her, along with other themes of multilingualism and linguistic rights. She’s recently spoken out about being requested to remove the phrase ‘cultural genocide’ or references to persecuted minority groups from an address before the UN.

Ofelia García: Dr. Ofelia García is a Professor Emerita of Urban Education and Latin American, Iberian, and Latino Cultures at the CUNY Graduate Center. She’s also been a professor and part of leadership teams at Columbia University, Long Island University, and City College of New York. Her work in bilingual education and bilingualism began with her personal experience of moving to New York from Cuba when she was 11 years old, later teaching bilingual students herself. She has published at least twelve books on bilingual and multilingual education and language learning.

Spanish

Spanish

French

French

Italian

Italian

Arabic

Arabic

Portuguese

Portuguese

German

German

Chinese

Chinese

Japanese

Japanese

Russian

Russian